Another Eurovision Storm: Charlie McGettigan Joins Nemo in Returning His Trophy

Eurovision keeps finding new ways to test the patience of its own community, and the latest chapter is one for the history books. What began as a symbolic gesture from Nemo —who won the contest for Switzerland in 2024— has now turned into a small but growing rebellion among former champions. Nemo’s decision to return the Crystal Microphone in protest at the European Broadcasting Union’s stance on Israel’s participation seems to have struck a deeper chord than the EBU might have expected.

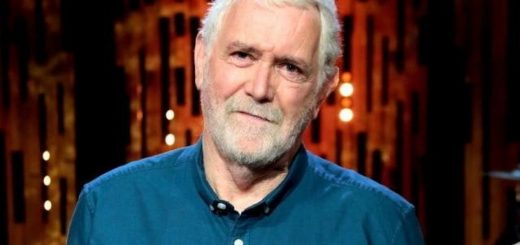

And now, Charlie McGettigan, Ireland’s 1994 winner alongside Paul Harrington, has decided to follow suit.

A second trophy on its way back to Geneva

In a video shared through the Ireland–Palestine Solidarity Campaign, McGettigan announced that he too intends to hand back his Eurovision trophy. With a mix of resignation and quiet determination, he explained that supporting Nemo’s protest felt like the only honest thing to do.

He even joked that he can’t actually find the original trophy from 1994, but if he does, he’ll return that one too. Sometimes the smallest sentences carry the loudest weight.

For McGettigan, the reason is simple: continuing to include Israel in the competition, under current circumstances, is incompatible with Eurovision’s own values. In his words, the EBU is “ruining its own contest” in an effort to protect Israel’s image while public sentiment —and now artists— clearly reject this direction.

Nemo lit the fuse

Nemo’s original statement was already a turning point. They argued that Eurovision claims to stand for unity, inclusion and dignity, yet keeps a participant whose actions openly contradict those ideals. They cited the UN’s Independent International Commission of Inquiry, which concluded that Israel has committed acts of genocide in Gaza —a line with obvious moral and symbolic weight.

Nemo wasn’t subtle. Nor, it seems, did they intend to be.

The EBU responds… without really responding

Martin Green, the Director of the Eurovision Song Contest, eventually issued a comment through the BBC. His message was sympathetic in tone but deliberately empty in substance: Eurovision is “saddened”, the organisation “respects Nemo’s deeply held views”, and they remain “a valued part of the Eurovision family”.

Polite. Warm. And diplomatically evasive.

What the EBU did not do was engage with the accusation at the heart of Nemo’s protest —that the organisation has contradicted its own ethical foundation. Their response prioritised calm optics over confronting what has become a deeply uncomfortable moral debate.

Pressure mounts on Eurovision

As more artists speak out, the cracks become harder to ignore. Johnny Logan, Emmelie de Forest, Salvador Sobral —winners from three different eras— have all criticised the EBU’s handling of Israel’s participation.

Sobral, never one to whisper his opinions, called Portugal’s inaction “institutional cowardice”, arguing that what is at stake is not politics but humanity.

When a contest built on joy starts being defined by moral fracture, something is shifting. And not quietly.

A crisis that won’t go away

Two trophies being returned will not collapse Eurovision. But they do mark a moment the EBU can no longer dismiss as “online noise” or “temporary outrage”. This is no longer just the fans, nor the broadcasters, nor the press.

These are the winners —the people Eurovision itself places on its pedestal.

And when the champions begin giving their trophies back, the message is unmistakable:

Eurovision is losing the part of itself that made winning meaningful.

Source: X